A couple of words from our new proofreader in boss on the permanent impact of evolving landscapes.

Via presentation as Texas Month to month’s new manager in boss, I might want to enlighten you concerning a tattoo, and it’s not even mine. My granddad’s left shoulder was covered by a Longhorn’s head blasting through a five-pointed star. Over the star were the words “The Lone Star State,” and beneath it, in the event the message wasn’t adequately clear, was “Texas.”

A 25-year-old five-foot-ten, 150-pound Marine with previously diminishing hair, Confidential James Daniel “Dan” McCammon got inked in San Diego prior to delivery out for Hawaii and afterward Iwo Jima, where, as a forward onlooker, he was sent in front of the cannons with a loop of wire and a telephone to call for fire. He endured a couple of days before a shell detonated close to him, splashing him with shrapnel and causing transitory visual deficiency. He was cleared on board the USS Bolivar on Walk 6, 1945, alongside 450 different losses. That star and Longhorn were with him as the shells fell and afterward as the boat set out to arrive at Saipan.

When I went along, Dan was a family man who had put in years and years as a sales rep for an oil field administrations company, selling pipe out of an office in Dallas. He wore formal attire consistently. He never preferred the work, however he got a company vehicle and several club enrollments to engage clients. Also, accompanying him on each deal call and at each beverage after work, under his short-sleeved white button-down, was that striking statement of personality.

Dan was an entertaining, enchanting soul whose whole life was spent in the metropolitan limits of Dallas — with the exception of those apprehensive predeployment weeks in San Diego and those vicious days on Iwo Jima and, maybe generally significant of all, around twelve developmental summers as a youngster, cowboying on his uncle’s farm west of Tulia, in the Beg region of Swisher.

I was brought up in a similar 1922 two-room, one-shower home on Montclair Road, in a verdant North Oak Bluff area, that Dan had experienced childhood in. In the event that I’d been shipped off to a West Texas farm when I was growing up, my life would have been flipped around. My hypothesis is: No Beg summers? No tattoo. I accept my granddad’s tattoo memorialized what probably been a significantly influencing experience, that the experience gave him permit to get the tattoo — and that Iwo Jima caused him to get it before it was past the point of no return.

The direct I’m attempting toward make is that critical time on completely open land transforms you.

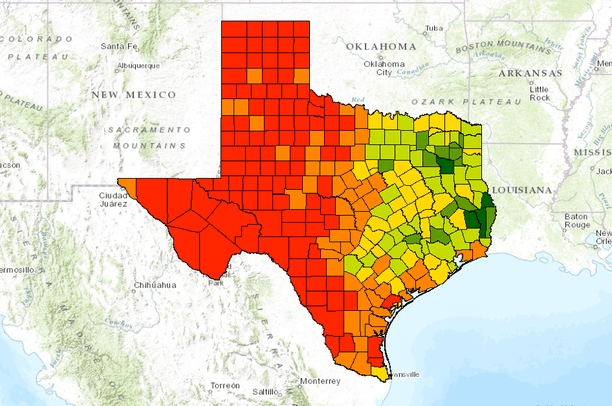

Ends up, as Emily McCullar’s main story about the eventual fate of one fire-desolated Texas farm clarifies, our completely open land is itself evolving.

Land is a valuable open door. Land is confounded. Also, land is, assuming that you stay in any one spot sufficiently long, inconvenience. In any case, it generally implies something.

There’s a statement close to the furthest limit of Emily’s story, about managing many dairy cattle that pass on all at one time, that caught me unsuspecting. I’ll allow you to find it for yourself. The statement — and the whole story — assisted me with understanding the stuff to claim land and why we purchase grounds, sure, however more significant, why it feels so persevering, in any event, when verdure and the creatures stroll upon and feed on it are consumed by fire. Why we can’t let it go.

Beg farms (and North Texas farms) and Lone Star State tattoos and Texas Month to month stories — these are enduring and lovely, whenever confounded, things. They were picked intentionally by confident individuals who might have headed something else altogether. What’s more, our state is more extravagant for them.

As I start this work, I need to say thank you for perusing regarding our consistently evolving state. We have such countless stories to tell. We go for the gold them to influence you profoundly and to persevere, similar to the Lone Star State itself.