Trump proposes land equity for Dark South Africans is a danger, yet US land seizures helping white populaces – past, present and future – are important and just.

In an all-too-recognizable showcase of obliviousness, US President Donald Trump as of late upbraided South Africa’s new Seizure Act, erroneously outlining it as a racially determined assault on the white minority. His comments, saturated with falsehood, reverberation the way of talking of extreme right gatherings that have long looked to delegitimise South Africa’s endeavors to address hundreds of years of land dispossession.

While Trump is completely justified to keep US help – cash South Africa neither depends upon nor looks for – he should not be meddling in a sovereign country’s endeavor to address verifiable foul play. His provocative remarks are not recently misinformed; they are risky. South Africa, a country that rose up out of the severe arrangement of politically-sanctioned racial segregation just quite a while back, remains profoundly scarred by racial and monetary imbalance. The land question is at the core of these unsettled injuries, and crazy statements from the US president risk kindling pressures in a general public actually making progress toward equity.

Yet, maybe the best incongruity of everything is that the US itself has seizure regulations under its Fifth Revision. The thought that land can be taken for public great, regardless of pay, isn’t new – it is primary to US property regulation. So why, then, does Best pretend shock when South Africa follows a comparative way?

This incongruity fails to measure up to Best’s comments about “assuming control over” Gaza and making it “our own” after Israel’s mass annihilation and destruction in Palestine. Seizing land inside one’s nation is a certain something; ethnic purifying and attaching unfamiliar land is pietism and moral debasement at an unfathomable level.

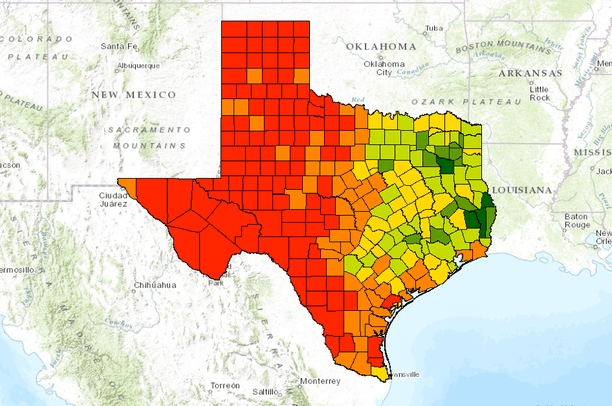

To get a handle on why land change is vital, one should defy an awkward truth: South Africa’s land was taken. From frontier triumph to politically-sanctioned racial segregation time constrained expulsions, Dark South Africans were efficiently seized and consigned to stuffed, fruitless “homelands”. The 1913 and 1936 Land Acts systematized this burglary, holding 87% of the land for the white minority and leaving the Dark larger part packed into only 13% of the country.

This isn’t old history. The outcomes of these regulations remain profoundly settled in. Today, notwithstanding making up 80% of the populace, Dark South Africans own main a negligible part of horticultural land, while white landowners – under 8% of the populace – still control by far most. The outcome? Around 64% of Dark South Africans stay landless, and millions live in casual settlements or packed municipalities.

Progressive post-politically-sanctioned racial segregation legislatures have endeavored to review this unfairness, yet progress has been agonizing. The “willing-purchaser, willing-merchant” model, presented during the 1990s, put the monetary weight on the state to purchase land at market rates. This methodology, while politically wary, has fizzled: land reallocation targets remain neglected, and monetary abberations keep on augmenting.

The Seizure Act looks to change that. It gives a lawful structure to land to be confiscated in unambiguous cases, including examples where the land is deserted, unused, or it was gained through past racial honor. Remuneration – when required still up in the air by thinking about variables like authentic procurement, state endowments, and public interest. At times, this implies land can be taken without remuneration.

This isn’t an assault on white ranchers. It is an important stage towards reestablishing nobility and monetary organization to the large numbers who were deprived of both.

Trump’s remarks didn’t arise in a vacuum. They adjust intimately with the account moved by white patriot bunches in South Africa – associations that have long looked to depict land change as an existential danger to white landowners. The “white decimation” legend, which dishonestly asserts that white South Africans are overall deliberately designated, has been entirely exposed. However it keeps on reemerging in traditional circles, enhanced by figures like Trump who blossom with stirring up racial complaints.

The realities recount an alternate story. There is no far and wide mission to hold onto land for arbitrary reasons, nor is the public authority participated in racial oppression. The Confiscation Act doesn’t give the state uncontrolled power – it basically adjusts South Africa’s land change system with protected standards of equity and value.

Yet, past the incorrectness of his cases, Trump’s impedance is risky. South Africa is as yet exploring its postcolonial character, offsetting compromise with compensation. Unfamiliar pioneers who foolishly embed themselves into this interaction – especially those without really any comprehension of the nation’s set of experiences – risk wrecking veritable advancement.

Maybe the absolute most glaring inconsistency in Trump’s position is the way that the US itself has seizure regulations. The Fifth Alteration of the US Constitution takes into consideration the public authority to hold onto private property for public use, gave that “just pay” is advertised. What is “just” is frequently discussed – similarly all things considered in South Africa.

Truth be told, US history is overflowing with instances of land seizures that were definitely more forceful than anything proposed in South Africa. Native lands were taken without remuneration dishonestly. Whole people group – especially poor and Dark areas – have been demolished through prominent space regulations for the sake of metropolitan turn of events. Assuming that the US sees no logical inconsistency in involving confiscation for its own advantages, for what reason is South Africa attacked for doing likewise?

The response is basic: land equity for Dark South Africans is treated as a danger, while land seizures that have generally helped white populaces are standardized.

Past its verifiable need, land rearrangement is significant for South Africa’s financial future. Without land, a large number of Dark South Africans remain kept out of monetary open doors. The capacity to cultivate, construct homes, or access credit is straightforwardly attached to land possession. However, under the ongoing framework, the abundance of the nation stays packed in the possession of a couple.

The monetary contention against land change – that it will frighten off financial backers or undermine the farming area – is a distraction. Nations that have effectively executed land change, like South Korea and Japan, have shown that reallocation, when done in a calculated manner, encourages financial development. The genuine peril lies not in confiscation, but rather in keeping up with the norm – where land is stored by a little tip top while millions stay landless.

Trump might take steps to cut US help, yet South Africa’s land strategies are not up for unfamiliar discussion. The nation’s hard-won power can’t be directed by a US president whose history on racial equity is wretched.

Land seizure isn’t burglary. It’s anything but an assault on white South Africans. It is the extremely past due rectification of a verifiable wrongdoing that denied Dark South Africans of their land, their nobility, and their financial future. Trump’s remarks are an update that the fight for equity will continuously be met with opposition – however South Africa’s way to compensation not entirely set in stone by outcasts.

South Africans will choose South Africa’s future.